October 23, 2023

The global economy has shown remarkable resilience, but low-income countries are suffering from the scars of recent shocks

Nea Tiililä, Economist at Finnfund

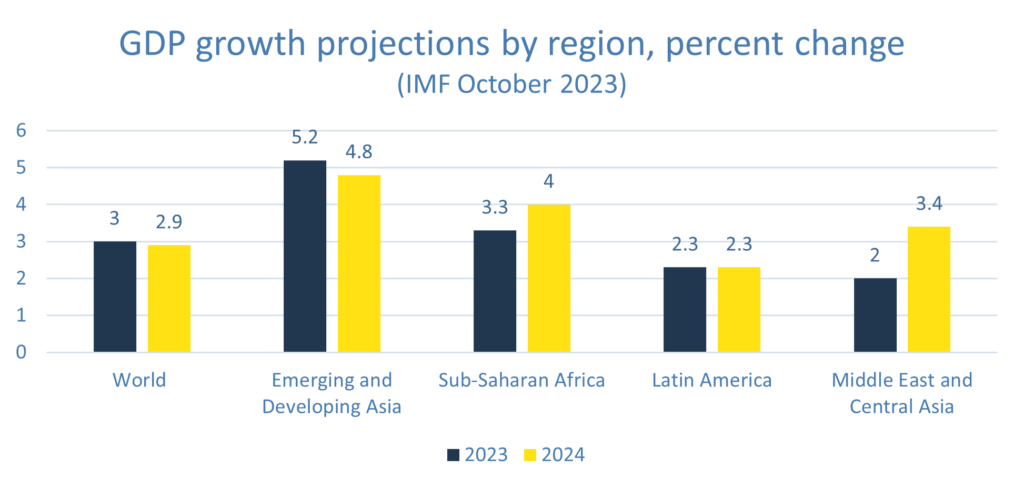

The global economy has undergone unusual crises and volatility over the past years. According to the IMF’s just-released outlook, the global economy has shown resilience and continues to grow but at a slowing pace. The recent slowdown is more pronounced in advanced economies than in emerging and developing countries. Overall, global growth in 2023-24 will be moderate compared to the historical average. The IMF points out that medium-term growth prospects have systemically weakened since the global financial crisis, especially for emerging markets and developing economies, implicating a slower convergence toward the living standards of advanced economies.

Emerging and Developing Asia continues to be the fastest growing region in 2023-24, however, growth forecasts are revised down due to economic uncertainty in China. Latin America’s growth is still relatively slow this year and next year. In contrast to the global trend of slowing growth, Sub-Saharan Africa’s growth is expected to accelerate next year despite the fact that the largest economies, Nigeria and South Africa, are growing very slowly.

Fast inflation and tight monetary policy are the main drivers for slowing growth

Inflation has started to gradually decline, but core inflation has been more persistent than expected. Thus, the interest rate environment will remain higher for longer. Globally, the IMF expects inflation to come down to target levels by 2025 without a major recession. However, there are a number of countries that have fallen into a crisis as a result of economic turmoil. Financial conditions have started to ease in many countries, but tight monetary policy in advanced economies continues to weigh on some developing countries 2023-24 as capital flows have not returned to the developing world, external sector pressure remains elevated, and currencies continue to face depreciatory pressure.

The ongoing weather phenomenon, El Niño, increases upside risks for inflation, especially in developing countries. El Nino disrupts crop cycles, and thus, can decrease food output, which would entail accelerating food inflation. The impact of rising food prices would be felt especially in Sub-Saharan Africa, where food contributes around 40% of total consumption. [Finnfund is playing a role in improving food security through our investments in sustainable agriculture that support domestic food production in low-income countries and thus reduce the dependency on imported food.]

China is facing a structural slowdown

Another driver for the slowing growth is China. China contributes around 35% of global growth, and thus, the economic slowdown in China is reflected in global growth numbers. Now, it looks like China is facing a structural slowdown in its growth. This is due to a shrinking population, property sector challenges and high indebtedness but also as a result of a policy shift under President Xi. China has increasingly focused on internal, external and security policies over economic policies. Thus, China is not expected to reach its pre-pandemic growth levels in the medium term. China’s outlook is highly dependent on the policy measures of the Chinese authorities. In the short-term, China’s economic slowdown will negatively impact its main trade partners, including many advanced economies and Asian countries, and commodity exporters. On the other hand, the economic problems in China can lead to increasing FDI to other emerging Asian countries as investors are moving their money away from China.

Debt risks are not going away

Debt vulnerabilities in developing countries have been rising for multiple years. As a result of the pandemic and the Russia-Ukraine war, fiscal buffers have eroded, debt levels have peaked, financing costs increased, and growth has slowed down for multiple years. There is a huge need for financing, especially now, as investors have sought less risky investment destinations from advanced economies. At the same time, 56% of low-income countries and 25% of emerging markets are considered at high risk of debt distress and would need funding to refinance upcoming liabilities. 2023 has surprised positively in the sense that there have not been any new sovereign debt defaults. However, the risks are not expected to vanish any time soon. The coming years will be difficult, especially in Africa, where multiple Eurobonds will mature in 2024-25. Countries with a high risk of default include, for example, Ethiopia, Tunisia, Egypt, Kenya and Pakistan.

More information and media contacts:

Economist Nea Tiililä, nea.tiilila@finnfund.fi, tel. +358 50 520 2203

Communications Director Unna Lehtipuu, unna.lehtipuu@finnfund.fi, tel. +358 40 624 0896