November 12, 2020

Beyond avoided emissions, DFIs seek carbon removals

For quite some time, it has been acknowledged that global CO2 emissions need to be reduced to avoid the catastrophic effects of climate change. Today, many companies, development finance institutions (DFIs) and other investors operating in developing countries are increasingly interested in tracking their CO2 emissions and taking action to reduce them. However, lack of action on a global level has led us to a situation where emission reductions are not enough. We need carbon removals – and better measures and tools to account for our carbon budgets.

It is a clear case. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report (2018) shows that when the carbon dioxide content in the atmosphere is limited to 420 parts per million (PPM), we have a 66% chance of limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees. In 2019, the average carbon (referring to carbon dioxide, or CO2) content in the atmosphere was 409 PPM (NASA 2020). This meant that there was a margin of only 11 PPM left in our carbon budget, which was the sum of all emissions and removals. In recent years, the carbon content has increased by 2.5 PPM annually (NASA 2020). At this rate, we will use up our global carbon budget within the next 5 to 10 years.

Unfortunately, the level of needed to keep us within the carbon budget is basically impossible to achieve. The COVID-19 lockdowns we recently experienced, largely closed many parts of the world for months, but this was not enough to take us to the necessary of reduction. Despite the COVID-19 lockdowns, the atmospheric carbon content is estimated to increase by an additional 2.3-2.4 PPM in 2020, which is only marginally less than the 2.5 PPM increase in the previous years.

We need to pull back the CO2

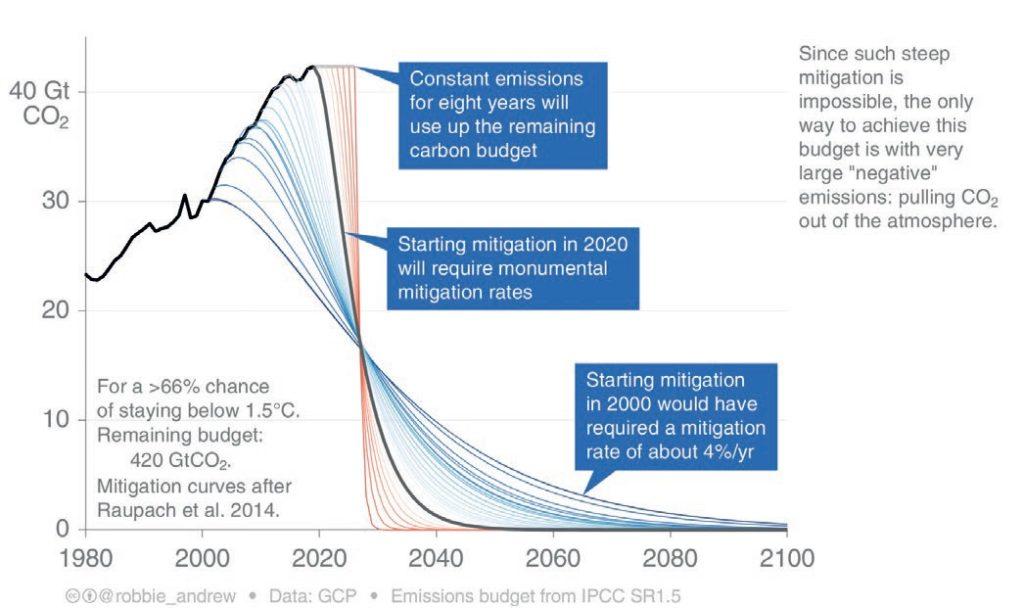

To stay within the 1.5 degree carbon budget, we would need a reduction of almost 15% in emissions every year. Thus, we would need a permanent lockdown every year and an additional systemic change to stay within the budget. The only example of when such a reduction took place was the collapse of the Soviet Union. Now we need similar emission reductions without the collapses of economic and social welfare. Figure 1 illustrates this problem.

Figure 1 – CO2 mitigation curves: 1,5°C

While we do not want to be too pessimistic about this, the facts must be recognized. Although the 1.5 degree target is most probably beyond being attained, it does not mean that we should stop acting. On the contrary, 1.6 degrees is better than 1.7 degrees, and so forth. In terms of increased temperature, every one-tenth of a degree avoided is crucial. The IPCC report (2018) shows that the difference between 1.5 degrees and 2 degrees means that we could save at least 10-20% of the world’s coral reefs and reduce from 37% to 14% the world’s population that will be exposed to extreme heat, as well as limiting other negative impacts caused by climate change. So how will it be possible to stay within the budget or not to overshoot it significantly? The only option is to actively use carbon removals. We need to pull CO2 back from the atmosphere.

Carbon budgeting as means to achieve strategic goals

Carbon budgeting means that a budgeting unit accounts for a company’s carbon removals and emissions in a coherent, internationally accepted manner. For an investor, carbon emissions consist of plus emissions from investment. An impact-minded investor can use carbon budgeting as a tool to steer its operations towards its strategic goals, and eventually, carbon neutrality. For example, some financial institutions have set a target to reach carbon neutrality by 2050. The chosen target year defines the pathway to reaching the goal.

As the world still largely depends on fossil fuels, and every investment generates some emissions, investors need carbon removals to achieve carbon neutrality. The sooner the target year for carbon neutrality is, the more obvious it is that carbon removals are needed to reach the target. In addition to mitigating climate change, an investment in carbon removal projects can provide positive economic development and other measurable impacts.

Huge opportunity for investors – and investees

Carbon removal and climate mitigation projects provide significant opportunity for project developers, companies, and investors. When comparing the costs of these projects, it is worthwhile noting that in terms of climate effects, it is often significantly cheaper to invest in climate mitigation projects in developing countries than in developed countries: in developed countries many of the low-cost activities have already been secured, and the structural changes that would be needed for redevelopments are often costly, both economically and politically.

If a country or company decided to take economic advantage of investing in climate projects in developing countries, where could they find the experience and capacity to finance them? In many cases, it is with the DFIs. Climate change mitigation projects, such as renewable energy and energy efficiency, have been great successes for the DFIs. These projects fit within the mandate of the DFIs, as they are usually economically viable, socially and environmentally sustainable, and generate economic growth and other measurable impacts.

Over the years, DFIs have successfully invested in a wide range of companies with significant emission reductions, and have played a major role in developing the investment environment for renewable energy projects in developing countries. They have also seen more and more fully commercial financiers step in. Now it is time to do the same with carbon removal projects.

The answer lies in sustainable forestry and agroforestry

Currently, the only economically viable means to generate carbon removals is sustainable forestry and agroforestry. Other means of removals, such as direct air carbon capture and storage, as well as bioenergy with carbon capture and storage have not proven to be economically viable.

With forestry and agroforestry projects, as the trees grow, they sequester carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere. In our experience, the largest removals are achieved with afforestation projects, for example, when land is converted from grassland to forest land. The forest stores carbon in two ways: one is within the biomass comprising the forest, and the other is within the forest products, such as wooden constructions. Agroforestry combines forestry and agriculture; for example, the land is used for crop (such as coffee) production, and the trees provide both income and shade for the crops.

From an investor’s point of view, afforestation projects – such as sustainably managed forest plantation and agroforest companies – have proven to be attractive business cases: these companies plant the trees for commercial use. Responsible practices – such as making good relations with local communities their top priority – are key. In many developing countries, and particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, land use and food security are prominent issues, not only because of increasing populations, but also because of the increasing effects of climate change.

In terms of carbon, responsible companies provide permanency of carbon storage, as they do not harvest more than the trees grow. From the sustainably harvested trees, the companies produce poles, sawn wood, panels, energy wood and other types of wooden products. The permanency of carbon storage depends on the products. For example, in Africa carbon is stored in the electricity poles for 25 years on average. So far, there have been challenges in accounting for carbon removals, as the current, publicly available methodologies and tools have not been suited to the needs of financial institutions. Furthermore, they have not provided the accuracy that would be needed to adequately account for carbon removals.

A new tool for forest carbon sequestration is under way

At the beginning of 2020, Finnfund started discussing with some other DFIs, the methodologies and challenges involved in forest carbon accounting, and we noticed that we were not alone. We thought we could do better, though, so we teamed up with colleagues from CDC, FMO, Swedfund and Simosol Forestry & Software consultancy, in order to develop a comprehensive methodology and a new forest carbon sequestration tool (FRESCOS). With the tool, one can measure total carbon removals, by accounting for changes in the carbon stocks, such as forest biomass and harvested wood products.

This new tool is needed for two purposes: scenario analysis and ex-post annual accounting. The scenario analysis functionality is used for due diligence purposes and to estimate the total and expected annual amount of carbon removals for a single project. The ex-post annual accounting functionality is used to monitor the absolute carbon removal of a project; this can further be used to analyse the carbon neutrality of a project portfolio. The FRESCOS project is due for completion by the end of 2020, and our investees and other stakeholders are invited also to use the tool, and eventually, to develop it further.

It is a Win-Win-Win deal

At Finnfund, we have noticed that many forestry and agroforestry companies find it useful to demonstrate the climate effects of their operations. Their investors and clients are increasingly interested in carbon removals, and accounting for emissions is increasingly on everyone´s agenda. By providing information on carbon removals, investors can see the potential and the additional benefits in relation to their climate strategy.

To illustrate this, just ask company executives whether they would like to communicate to investors that a particular project is pulling CO2 from the atmosphere instead of emitting it – and listen to what they have to say.

The market for carbon credits – where a company compensates for its own emissions by earning carbon credits from carbon removals – is growing. With the new FRESCOS tool, we are happy to help our investees to account for their carbon removals, as well as to support them in developing their businesses, and in growing their revenue from the compensation markets.

Conclusion

To sum up, companies win, as carbon removals can provide new access to finance and generate additional revenue. Investors win, as a better understanding of, and accounting for carbon removals can provide both a significant boost to meeting their strategic climate goals, and additional opportunities for investment. Humanity and the Earth win, as the globe becomes a cooler and greener place.

Kenneth Söderling

Impact Analyst, Finnfund

Kenneth Söderling is an Impact Analyst at Development impact team at Finnfund, a Finnish development financier. He focuses on measuring impact and carbon accounting of emissions, avoided emissions and carbon removals, both on project and portfolio level. Kenneth holds a masters’ degree in environmental economics from University of Helsinki.

This article has been published in the special issue of Private Sector and Development on 6 November 2020.