June 27, 2022

A tale of surveillance – investor’s role in dealing with data confidentiality

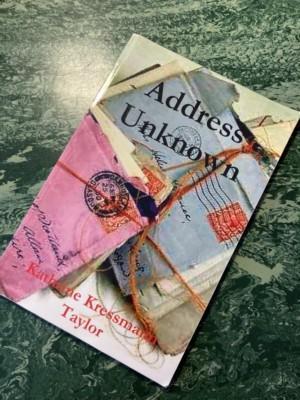

Address Unknown by Kathrine Kressmann Taylor.

For me, Address Unknown is one of those books that everyone should read, over and over. It is one of those books that resonate when I think about cybersecurity, user data confidentiality, telecom sector and democracy.

Despite the fact that the book was written in 1938, the basic idea is still, unfortunately, very topical today.

So what’s that book about? On its website, the Barnes and Nobles bookshop presents Address Unknown as follows: ”In this searing novel, Kathrine Kressmann Taylor brings vividly to life the insidious spread of Nazism through a series of letters between Max, a Jewish art dealer in San Francisco, and Martin, his friend and former business partner who has returned to Germany in 1932, just as Hitler is coming to power.”

For me this book is also about the consequences of surveillance of correspondence between friends and that’s why I link it to risks associated with the telecom sector or any sector that obtains, stores and uses client data: banks, online shops, hospitals, food delivery platforms, and so forth.

Connectivity is essential in today’s world, for all of us, everywhere. That’s the good story.

Now, connectivity also comes with challenges. Is someone reading my messages? listening to my phone calls? keeping a log of my messages? checking my address book and my network of friends and family? surveying how I use my money or how often I go to the doctor, and then, connecting the dots? Why would someone do that?

For me, Address Unknown is also the story to remember when thinking, for example, about the human rights impacts of Telenor’s exit from Myanmar. (At this point, I must clarify that I or Finnfund do not have any connection to Telenor but the case has been in the media and gained international attention.)

When Telenor invested in Myanmar, the future of democracy in the country looked bright – even if the military had retained key ministerial posts and presence in the parliament. There was a rush to invest and establish in the country and no one really expected a full return of the military.

So, Telenor, a Norwegian telecommunications company, established a subsidiary in Myanmar and became the operator of choice for activists and opponents of the military who expected their information to be kept safer than with local telecom companies.

And then… In July 2021, after the military coup in Myanmar, Telenor decided to exit the country for human rights reasons – and then… the authorities interfered in the choice of the buyer. As stated in this article by Wired, this can have consequences for people, and in particular, activists and opponents of the military regime.

The final regulatory approval for the sale was given in March 2022 with the condition that the buyer M1, a Lebanese investor group, would partner with Shwe Byain Phyu, a local conglomerate with alleged ties to the military. Since then, M1 has further transferred a number of shares to Shwe Byain Phyu, which will now have a majority control (of 80% stake) in Telenor Myanmar. Some of the customers have already been asked by the authorities to reregister their accounts, which can often be an indication of a growing surveillance.

It’s Myanmar, it’s Telenor, but it could have been in another country and another company.

That is the reason why we at Finnfund take these issues seriously and integrate data security and confidentiality in our human rights risk assessment, when investing in sectors that access and manage confidential client data.

We discuss data security, data confidentiality, IT systems, surveillance risks, and local legislation with our potential and existing investee companies. We also want to make sure the company can demonstrate it has the right systems to mitigate the risks that exist or can be foreseen. For example, we expect our microfinance companies to comply with Client Protection Principles, that address, among other issues, data security.

As an active, responsible investor we monitor and discuss these issues and the implementation of policies and principles in practice and – understanding that our investee companies may have legal obligations to surrender client data to the authorities – we expect them to publicly report the number of such situations.

However, as we can see in the case of Telenor, we must acknowledge, that, we may not forecast all the changes and all the challenges that, eventually, an exit can bring. This is the case everywhere, but I would say, particularly in fragile contexts.

As an impact investor and development financier, we aim to generate long-lasting positive impacts to foster sustainable development. Therefore, at Finnfund, we are also increasingly paying attention to how positive impacts and responsible business practices are sustained also when our involvement (and financing) has come to its end, hence after we have exited the investment. In practice, in our equity investments this can mean, for instance, discussions with the investee and potential buyers, and at the end of the day, also a consideration of to whom and when we sell our shares.

We may not be able to forecast the future, but our job is to do our best to manage the risks.

Sylvie Fraboulet-Jussila

Senior environmental and social adviser

This text has originally been published on Finsif’s blog in May 2022.